Table of Contents

- Fermat’s little theorem

- Finding Greatest common divisor (GCD)

or Highest Common Factor (HCF) - Sum of series

- Permutations & Combinations

Fermat’s little theorem

If \(p\) is prime, for any integer \(a\), then \(a^p-a\) is divisible by \(p\). If \(a\) is divisible by \(p\), this is trivially true.

\[a^p \equiv a\ (\textrm{mod}\ p)\]If \(a\) is not divisible by \(p\), then \(a^{p-1}-1\) is divisible by \(p\) as well. In other words, the remainder of \(a^{p-1}\) when divided by \(p\) is 1.

\[a^{p-1} \equiv 1\ (\textrm{mod}\ p)\]Example usage of fermat’s little theorem

Takeaway: Simplify \(a^n\ \%\ p\) to \(a^r \ \% \ p\), where r is \(n \ \% \ (p-1)\) if p is prime.

Say we want the remainder of \(3^{100,000}\) with \(53\) where \(53\) is prime.

We know that, \(a^{52}\%53 = 1\). We can write, \(3^{100,000}=(3^{52})^{q}*3^r\) where \(100,000 = q*52+r\). Programmatically,

q = 100_000 // 52

r = 100_000 % 52

We can ignore \((3^{52})^{q}\) as the remainder will be \(1\) multiplied by \(1\), \(q\) times, ie., \(1\). So \(3^{100,000}\ \%\ 53=3^r\ \%\ 53\). In this example, r is 4. So the answer is \(3^4\) % \(53\) or \(81\ \% \ 53\) which is 28.

Mathematically, this can be written as

\[3^{100,000}=(3^{52})^{1923} \cdot 3^4\] \[3^{52} \equiv 1\ (\text{mod}\ 53)\] \[(3^{52})^{1923} \equiv 1^{1923}\ (\text{mod}\ 53)\] \[(3^{52})^{1923} \equiv 1\ (\text{mod}\ 53)\] \[(3^{52})^{1923}\cdot 3^4 \equiv 3^4 \ (\text{mod}\ 53)\] \[3^{100,000} \equiv 81 \ (\text{mod}\ 53)\] \[3^{100,000} \equiv 28 \ (\text{mod}\ 53)\]Finding Greatest common divisor (GCD)

or Highest Common Factor (HCF)

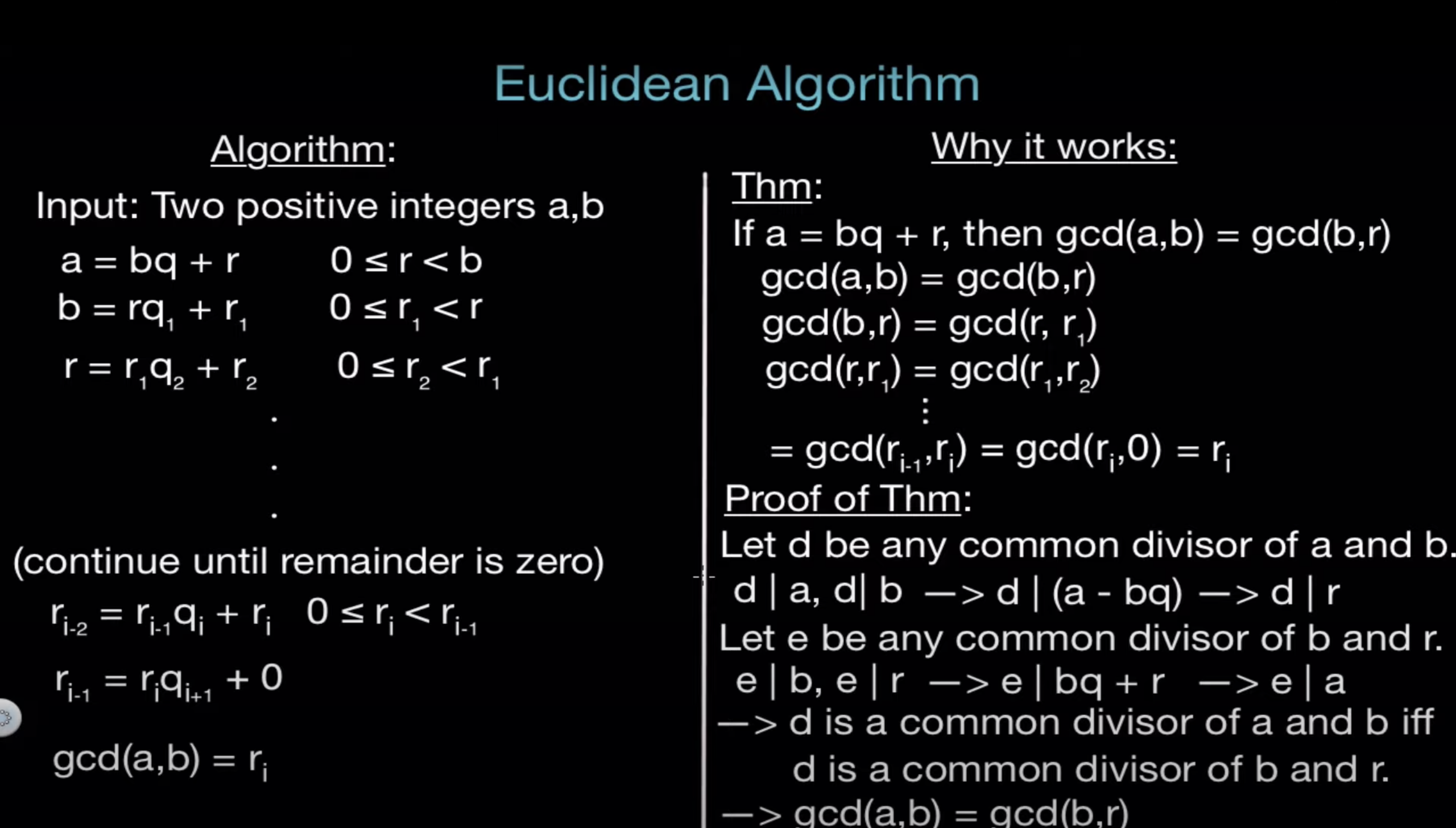

The key here is the Euclidean algorithm. \(gcd(a,b) = gcd(a,b-a)\). That is GCD of two numbers is the same if we subtract the smaller number from the bigger. We can repeatedly subtract the smaller number from the bigger number without sacrificing correctness.

Proof: Let \(p\) be the GCD of \(a\) and \(b\). We can write \(a\) and \(b\) as \(a = p \times m, b = p \times n\). Now, \(a-b=p\times(m-n)\). As we can see the GCD is preserved. Repeatedly subtracting merely changes the coefs of \(m\) and \(n\). For instance, \(a-b-b=p\times(m-2n)\).

We can make the above faster by using modulo instead of subtraction.

def gcd(a, b):

if a == 0:

return b

return gcd(b % a, a)

Sum of series

Natural numbers

\(\begin{align*} 1 + 2 + 3 ... + n = \sum_k^n k &= \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\\ 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 ... + n^2 = \sum_k^n k^2 &= \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6} \end{align*}\)

Geometric series

\(\begin{align*} 1 + r + r^2 \ldots + r^k &= \frac{1-r^(k+1)}{1-r}, r\neq 1 \\ 1 + r + r^2 \ldots + r^k &\leq \frac{1}{1-r}, r < 1 \\ &\leq r^k \left(1 + \frac{1}{r-1}\right), r>1 \end{align*}\)

Inequalities tell us that when

- \(r < 1\), first value dominates and the total is upper bounded by a constant.

- \(r > 1\), the sum is a constant times the highest power in the series

Other series

\(\begin{align*} 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \ldots +\frac{1}{n} = \sum_{r=1}^n \frac{1}{r} &\approx \log n \end{align*}\)

Permutations & Combinations

1.a Permutations

Number of ways to seat \(n\) persons in \(n\) positions: \(P(n) = n!\)

For instance 4 persons A, B, C, and D in 4 chairs: \(P(4) = 4!\)

1.b Permutations

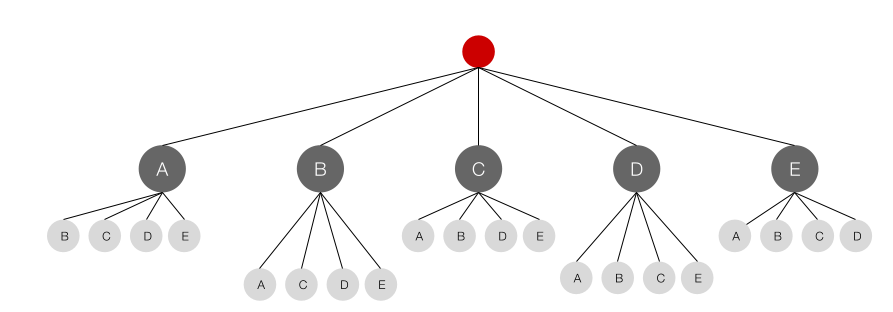

Number of ways to seat \(n\) persons in \(r\) positions. \(nP_r = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!}\)

For instance 5 persons A, B, C, D, and E in 2 chairs. \(5P_2 = \frac{5!}{3!} = 5 \times 4\)

Another way to see this is, the first chair there are 5 options and for each of those 5 options we have 4 options.

2. Combinations

We have \(r\) seats, what is the number of ways to choose \(r\) people to seat from \(n\) people? We don’t care about the order in which they sit. This is the number of ways we can seat \(n\) people in \(r\) seats (\(nP_r\)) divided by the number of ways we can arrange \(r\) people in \(r\) seats.

Say we have 6 people and 3 seats. Number of ways we can choose 3 amongst the 6 to seat is number of different ways we can seat the 6 people in 3 chairs \(6P_3\) divided by the number of ways we can arrange 3 people in 3 seats ie., \(3!\); \(6C_3 = \frac{6!}{3!3!}\).

\[nC_r = \frac{nP_r}{r!} = \frac{n!}{r! (n-r)!}\]